Write tests. Instead of clicking. Mostly integration.

I love automated testing. There are few things that give me more satisfaction than a well designed and green test suite. Imagine my irritation when a rather negative sentiment against unit tests (and to some extent automated testing in general) has emerged across the development community. The start was marked by a tweet by Guillermo Rauch a long time ago:

It was picked up by Kent C. Dodds, who formalized the thought into the Testing Trophy, an opposition to Martin Fowlers Testing Pyramid. And as much as I enjoyed going through Kent's Testing Javascript course, the thought of my beloved unit tests being just a burden triggered a visceral reaction. Even more so did David Heinemeier Hansson's TDD is dead. Long live testing. [1], that led to a very interesting discussion between him, Kent Beck and Martin Fowler.

A summary of the arguments that are flowing through the ether:

None of those happen to me! They are all wrong! This article was going to debunk all those myths and tell you how to do unit tests the right way! I dug into the different (very fuzzy) definitions of the different levels of testing to find the blind spot. The one thing that everybody else missed and I magically discovered, that allows me to draw so much value from unit tests.

Instead, I found out that I'm writing barely any unit tests 😅

What is a unit test?

Martin Fowler's article makes clear from the get-go that there is no single clear definition. First of all the definition of unit itself is very fuzzy, since it strongly depends on the language and environment. It might be a class, a service, a function, a visual component or anything else. That set aside, he outlines some traits that are expected from unit tests:

The tests that I consider unit tests match all of those, as far as "match" is the appropriate term. They are lower than the full system, they are fast enough so I repeatedly run them and they are written by me. But actual "unit test rules" I have seen being enforced in teams paint a different picture:

From that angle, almost none of my tests apply to this category. I have to leave theory behind and investigate my practices that have grown over the years a little more closely.

Example scenario#

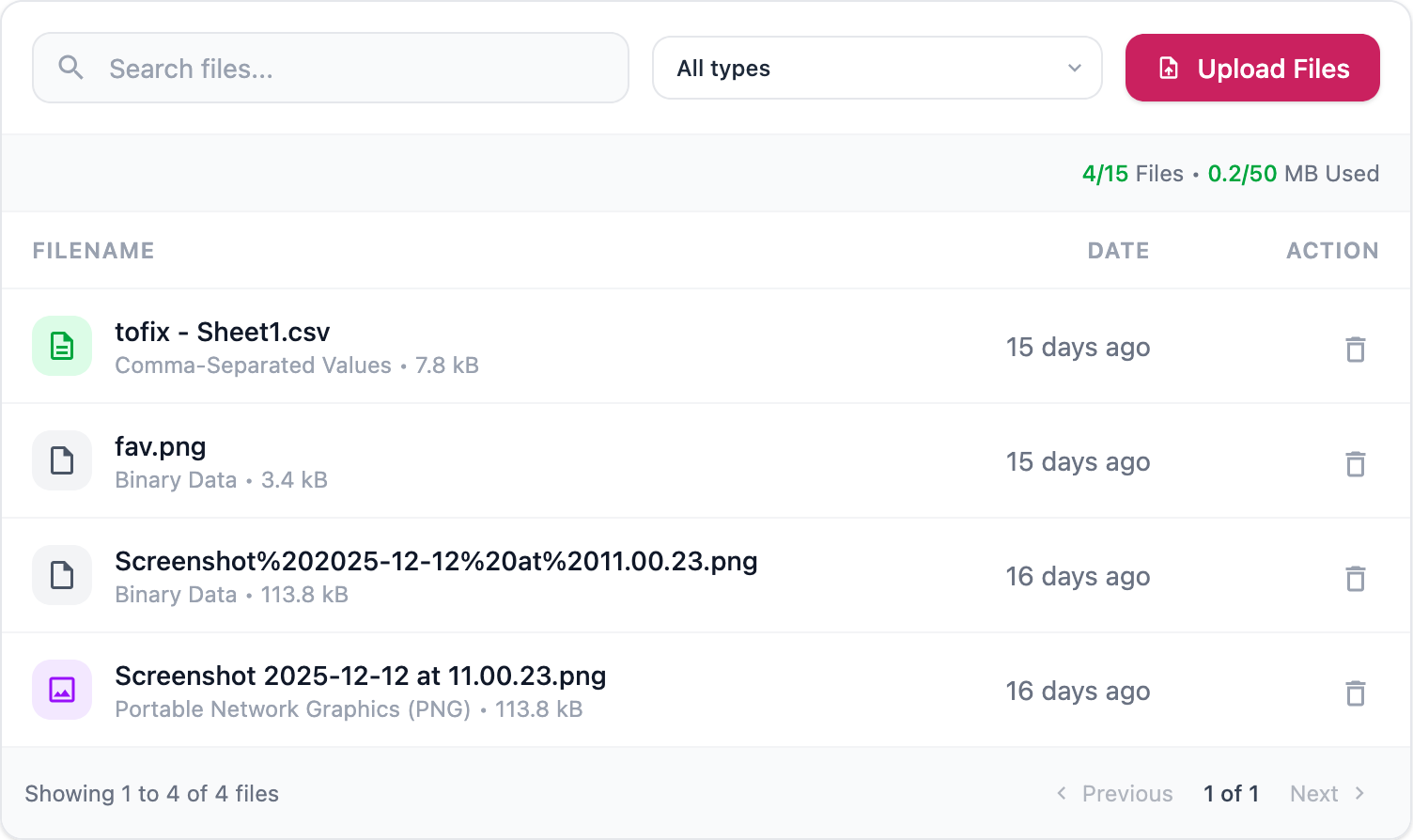

Let's walk through a very simple task I recently worked on. The host application consists of a Drupal data backend, a React frontend and a GraphQL API between them. The goal was to provide simple document management features, covering the following requirements:

A screenshot of what the UI looks like:

Typing#

The starting point is a GraphQL schema and operation definitions. For the sake of brevity, I'm only printing the top level schema and operations here.

scalar Upload

type Query {

listFiles(

name: String

type: String

limit: Int!

offset: Int!

): FileListResult!

}

type Mutation {

uploadFile(file: Upload!): UploadResult

deleteFiles(fileIds: [ID!]!): DeletionResult

}

query ListFiles($name: String, $type: String, $limit: Int!, $offset: Int!) {

listFiles(name: $name, type: $type, limit: $limit, offset: $offset) {

total

totalSize

files {

...File

}

}

}

mutation UploadFile($file: Upload!) {

error

file {

...File

}

}

mutation DeleteFiles($files: [ID!]!) {

error

files {

...File

}

}GraphQL Codegen is going to turn this straight into type definitions. The

FileListResult, UploadResult and DeletionResult become Valinor DTO's to

be used in the Drupal GraphQL resolver, while the ListFiles, UploadFile and

DeleteFiles operations generate type definitions that I can use in the

frontend components. This creates a contract between Drupal and React that is

enforced by the static type checkers: PHPStan and Typescript.

Drupal Backend#

The Drupal side of the implementation consists of simple Symfony service methods that map the input to the relevant operations in Drupal's ORM layer (aka the "Entity System") and validate their output against the expected Valinor output type. It has the following test cases:

They effectively cover 100% of the service implementation. But what's more interesting is how they are implemented. In those cases, Vitest sends raw HTTP requests to the API endpoint. Hence, they are not even close to unit tests. I would actually prefer them to be kernel tests, a Drupal specific test case type that bootstraps a minimal kernel and allow me to selectively enabled services and modules. That's a great way to write targeted and cleanly isolated test cases while largely avoiding mocks.

Unfortunately Drupal's "site building" philosophy gets in the way here. The canonical approach for data modeling in Drupal is to configure so called "entity types" along with their fields in the administration backend and then export that configuration to YAML files that then can be imported in any other environment. But this set of YAML configuration files is treated as a monolith by default and there is no easy built-in way to modularize it. This leaves me with three compromises to choose from:

I regularly go for option three, involuntarily agreeing with David to not compromise design simplicity for the sake of fast tests. When the number of edge cases to test goes over a gut-feeling threshold, I tend to encapsulate logic into services that I can properly unit- or integration test, so less of these expensive API tests are necessary. I have to begrudgingly accept that this very much matches an "outside-in" testing approach DHH also promotes in the discussion with Martin and Kent. I think I would have an easier time to accept this if his way to communicate would be a little more subtle. Apparently I am not immune to reactive devaluation.

React frontend#

When it comes to React components, the traditional way of unit testing would

involve a test runner like Jest in combination with a virtual DOM

implementation like jsdom. This would be the fastest running tests with the

least outside dependencies and even a completely mocked browser environment. But

this approach again is very prone to testing internals (e.g. id attributes or

specific classes as a proxy for visual appearance) and does not really reflect

the outside interface we want to establish.

Instead, my frontend tests again operate on a higher level. Storybook and it's

play functions are the workhorse for almost everything. Components run in a

real browser, and the API inspired by testing library allows me to write my

tests in a way that actually reflects usage of the component and not it's

internals. For example type "John" into the field with label "First name" or

click the button called "Next". This is way less of a maintenance burden since

I only have to change the test when the actual behavior of the interface

changes. It also makes sure the implementation meets at least some basic

accessibility standards, since the test API makes it hard to test things that

are not properly accessible. An example of such a play function:

export const Loading = {

play: async ({ canvasElement }) => {

const canvas = within(canvasElement);

// Verify loading state is shown

await waitFor(async () => {

await expect(canvas.getByRole("progressbar")).toHaveAccessibleName(

"Loading files",

);

});

// Verify table has aria-busy="true" and aria-live="polite" during loading (accessibility)

const table = canvas.getByRole("table");

await expect(table).toBeInTheDocument();

await expect(table).toHaveAttribute("aria-busy", "true");

await expect(table).toHaveAttribute("aria-live", "polite");

await expect(

canvas.getByRole("button", { name: /Next/i }),

).toBeInTheDocument();

await expect(

canvas.getByRole("button", { name: /Previous/i }),

).toBeInTheDocument();

// Verify pagination is visible, but disabled during loading.

await expect(canvas.getByRole("button", { name: /Next/i })).toBeDisabled();

await expect(

canvas.getByRole("button", { name: /Previous/i }),

).toBeDisabled();

},

} satisfies Story;When it comes to loading or mutating data though, I go for a 100% mocking

approach here. I use the Typescript type definitions derived from GraphQL

operations to mock HTTP responses inside the Storybook component previews, using

either an actual useOperation hook that reacts to it's environment, or by

using mock service worker. It allows me to reproduce and visually

regression-test each state of the application with very high test performance.

For example:

This covers the UI layer from the actual user interaction down to the point where the underlying HTTP request is sent. From a test-level and breadth perspective, this is very similar to the Drupal API tests, and again, I use the amount of test cases as an indication when it would be a good idea to separate into sub-components or helper functions that are tested separately.

All of this completely covers the visual aspects as well. Storybook will show me an actual preview of all of these UI states that I can use to rapidly iterate on styling without having to go through the actual application. And chromatic helps with visual regression testing and receiving feedback from stakeholders.

End-to-end tests#

The last level of testing is done by Playwright in most cases and really tests

the full application, both during CI workflows as well as a cron-based test run

on a production-like deployment. Those tests are really slow, but due to the

strict typing and the broad coverage of backend and frontend tests, they also

need to be only a few. For this specific feature I just have a single E2E test

case: UploadSuccess that tests if a file can be uploaded and appear in the

list afterwards. This case tests if multipart file uploads work correctly and

the API and the frontend are wired up. That's enough to give me the confidence

to deploy to production on Friday evening.

Are those unit tests?#

Most of those tests match the loose definition of low level (just backend, just frontend), speed and written during development. But languages do not match, they are not strictly about one function or class, and coverage metrics are therefore often complicated. It really depends on who you are asking. But to clarify this for myself, I will not call those "unit tests" any more, with the rare exception of the actual complex "pure logic function" test case.

Test driven development#

Ok, I have to admit that strictly by-definition unit tests are less common and

helpful than I would have thought up until now. I considered a lot of tests that

I have been writing unit tests, because they are not full system tests and

because that word got somehow stuck in my mind since university. For sure, there

are pure logic based components that require one, but in this whole feature, I

have a single real unit test. One that dynamically truncates file names

while preserving the extension (like my_very_very_long....tsx) and deals with

some edge cases. With a strong typing foundation and all of those other tests

actually being integration tests by definition, the shape resembles very much a

testing trophy. I yield 🏳️

But I'm not caving when it comes to Test Driven Development. In contrast to some very vocal members of the development community, I do not think that it has to click. That some have a genetic pre-disposition to be able to work in a test driven way. Not more than you have to be born to do push-ups or brush your teeth. You just do it, because you know it pays off. Period.

I also don't think that TDD causes test induced design damage. It just get's mixed up and associated with dogmatically unit testing. You always have the option to move to a higher level test - as I did - to pay for less complexity with a little more test run time. Which will still always be faster and more reliable than than you testing each change manually.

In the feature example we looked at before, I work fully test driven at every step. Not because some religious cult indoctrinated me and I dogmatically stick to its rules, but because it is faster and more efficient than anything else.

Working backwards through the labyrinth#

Remember the ultimate hack on how to solve any comicbook labyrinth quickly? Start at the goal and work your way backwards! That's exactly what you do when writing tests first. Test Driven Development just makes you think about the expected outcome - the win condition -, without being biased by an implementation on your mind. It feels similar how writing clarifies ideas, helping you to find flaws in your implementation before you even start.

Yes, that goalpost might change in the process a couple of times, but this strategy puts the end result first, and you are less likely adding [insert random design pattern or library], just because somebody liked it on Twitter.

The only thing faster than typing is not typing#

The other aspect is implementation speed. Clicking through a wizard form to verify all edge cases work (or worse: all colors are correct) is an exercise in futility that I got tired of very quickly. This is true for the simple API tests and even more for Storybook interaction tests, and doubles up as soon as you hand that feedback loop to an AI agent.

The investment in test automation pays off within the next minute, not next month. The more you do it, the lower the initial cost gets.

Spicy take: Everybody starts to do TDD if you unplug their mouse. -- Moi

No more debuggers#

In the beginning of 2025, I put a lot of work into crafting my perfect Neovim debugging setup. And before I had a chance to put it into action, Claude Code released, turned my development process upside down and I did not use it ever. It just became way easier to tell the genie that "I suspect service X does Y when given Z, write tests to confirm or deny that.". Then you go to brew coffee (or in my case, help somebody with homework), and when you come back, there is probably enough information to fix the problem. Before somebody shouts TEST BLOAT!: You don't have to keep them! They can be a temporary utility for repeatedly inspecting the system under changed parameters until the solution is at hand. And an agent does this very, very well.

Coverage and confidence#

I happen to have a lot of confidence in my tests to tell me if the system is intact. I rarely measure code coverage, but it does converge towards 100% almost all of the time. Not because I jump through hoops to achieve that, but thanks to only writing code a test asked me to 🤷♂️. A natural side effect of not using your mouse to test manually.

Not everything needs to have a name#

We know that naming is hard, yet we try to put labels on things that are often misleading. In the discussion around the definition what qualifies as unit, integration or system tests, Kent Beck declares that the distinction is "not particularly useful". I would extend that to "actively harmful". The perception and reputation of Test Driven Development has suffered quite a bit from being associated with dogmatic unit testing and its deficiencies.

Writing tests does not have to be a chore and game of complying to coding standards. They are maybe the most valuable tool in the box. Do not spoil that by having arguments on the internet about made up names and misunderstandings.

Write tests. Instead of clicking. Mostly integration (whatever that means).

Footnotes#

-

Amplified by his signature aggressive-clickbaity tone. [↩]